The Talmud is Hebrew for “learning.” Interesting that the Torah means “teachings” and the Talmud means “learning.”

The Talmud is often what Yeshua refers to as the “traditions of men” in the New Testament. He rebukes the Jewish leaders for placing these traditions of men above the actual commandments of God. Yet, as has been noted on this blog, both Yeshua and Paul taught from the Talmud. What does this tell us? It should help us place the Talmud in context – there is wisdom within it. The Talmud can help provide insight into the details of how to carry out an actual written law. But they should never supersede the actual law.

The Talmud is divided into 6 different sections:

- Zera’im (“Seeds”), dealing primarily with the agricultural laws, but also the laws of blessings and prayers (contains 11 tractates).

- Mo’ed (“Festival”), dealing with the laws of the Shabbat and the holidays (contains 12 tractates).

- Nashim (“Women”), dealing with marriage and divorce (contains 7 tractates).

- Nezikin (“Damages”), dealing with civil and criminal law, as well as ethics (contains 10 tractates).

- Kodashim (“Holy [things]”), dealing with laws about the sacrifices, the Holy Temple, and the dietary laws (contains 11 tractates).

- Taharot (“Purities”), dealing with the laws of ritual purity (contains 12 tractates).

The belief is that God passed down to Moses an Oral Torah in addition to the written Torah. These words were restricted from being written down for centuries. They were only passed on orally from teacher to student. During the 1st century it became increasingly difficult to teach these laws due to Roman occupation and restrictions. When the Temple fell in 70 AD it was recognized that this Oral Torah was being forgotten.

In the years following the destruction of the Temple, Rabbi Yehudah the Prince began writing down the procedures for the Temple. This writing is the largest of the Talmud and known as the Mishnah. Keep in mind that the entirety of the Talmud was written many many years after the teachings of Yeshua were written down.

Over the next several hundred years, many rabbis began to expound upon the teachings and their writings were collected into two great bodies, the Jerusalem Talmud, containing the teachings of the rabbis in the Land of Israel, and the Babylonian Talmud, featuring the teachings of the rabbis of Babylon. These two works are written in the Aramaic dialects used in Israel and Babylonia respectively.

As Rabbi Yehudah wrote down the Oral Laws, he included the teachings of the rabbis around the main text. Notice the way in which this culture added commentary to their sacred writings. It is quite different that we might do today.

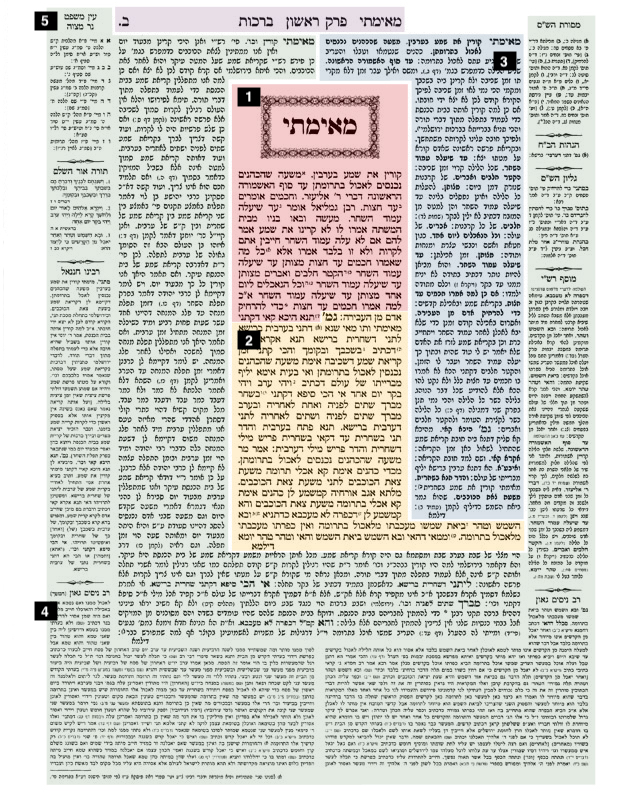

- The Mishnah

This is the first part of the page to review. It captures the ancient oral law of the Jewish people. Around the year 200AD -when Roman persecution threatened to break the spoken tradition – the leader of the Jews, Rabbi Judah the Patriarch, took the step of ordering the law to be distilled into a text to be memorised. - The Gemara

The Gemara, which in Aramaic means “to study and to know” is a collection of scholarly discussions on Jewish law dating from around 200 to 500AD. The discussions pick up on statements in the Mishnah (1) but refer to other works including the Torah. The Mishnah and Gemara combined constitute the Talmud as it is strictly understood.

The Gemara is written in Aramaic, and like the Mishnah lacks punctuation. However, there is a structure to the prose. Usually there is a statement, questions on that statement, answers and proofs. But rarely are the questions fully resolved. - Rashi

Students generally look at this section after reading a few lines of the Mishnah and Gemara. Rashi is a shorthand way of referring to Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, an 11th Century French scholar. He wrote one of the first complete explanatory commentaries on the Talmud.

Rashi’s words are usually rendered in a special font known as Rashi script and always appear on the inside margin of the page. - Other commentaries

The rest of the Talmudic page is taken up with commentaries by other rabbis from the 10th Century onwards. One section – the Tosafot, or “additions” – deals with difficult passages and apparent contradictions in the Talmud. Another section provides cross references to identical passages elsewhere in the work, and another directs the reader to rulings in medieval Jewish law that relate to that section of the Mishnah (1) and Gemara (2). There is also room for modern explanations and glosses on the language. - Page and chapters

The Talmud comprises six orders, which deal with every aspect of life and religious observance. It is further divided into 63 parts, or tractates, which are broken down into 517 chapters. This particular page is the first chapter of the first tractate in the Talmud, named Berakhot or “Blessings”. It is page two of the Talmud – the first page after the title page. In fact, it is referred to as 2a – the facing page will be 2b.

Chapter names are taken from the first word of the Mishnah (1), which is also shown in large font in an illustrated box. In this case the word is mei’mata or “From when” – the complete first line of this first chapter of the Talmud is “From when should we recite the Shema (‘Hear O Israel) in the evening time?”

Notice that the commentary encircles around the main text. This is a very cultural way to look at the Talmud. While the commentary encircles the Talmud, it is believed that the Talmud is like a fence around the Torah. The laws therein are established to prevent someone from getting too close to breaking any of the laws of the written Torah.

The sages who taught the teachings which make up the Talmud represented the totality of the sages of Israel. Because of this, and because the Talmud was accepted as binding by almost the entire Jewish people at the time, its laws are considered binding on all Jews no matter when or where they live. And it is precisely this binding that has kept the Jewish identity strong for thousands of years.

Leave a Reply